New Adjuvant Therapy Shows Promising Results to Treat Multiple Myeloma, B-Cell Malignancies

Written by |

A new class of drugs that activate a protein in cells’ endoplasmic reticulum may be used as an adjuvant therapy to treat B-cell malignancies, according to the study “Agonist-mediated activation of STING induces apoptosis in malignant B cells,” published in Cancer Research.

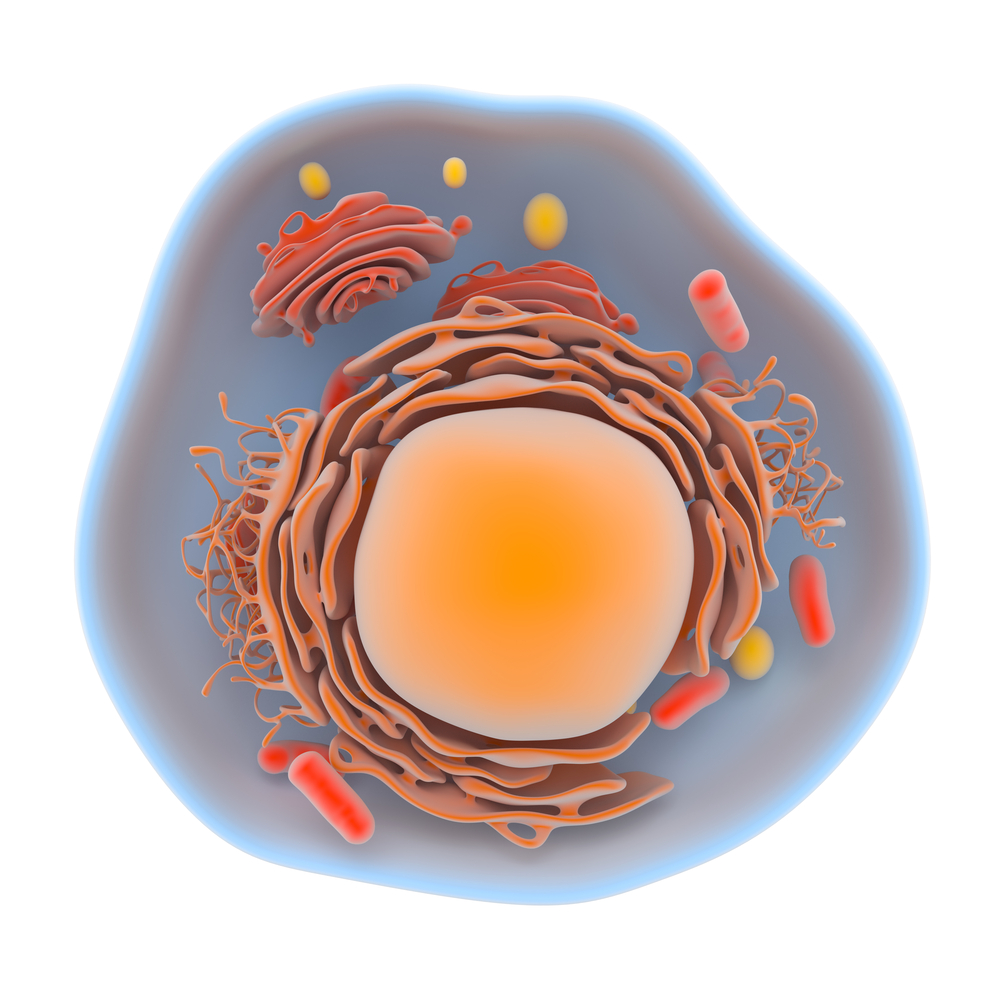

The cellular endoplasmic reticulum is a network of continuous membranes that control metabolism as well as the folding, assembly, and secretion of proteins, critical steps for the correct function of proteins. The endoplasmic reticulum is particularly important in the production of proteins involved in cell-cell communication, which has led scientists to focus on these membranes to find new ways of stimulating immune responses against malignant cells.

The protein STimulator of INterferon Genes (STING) resides in the endoplasmic reticulum and is a critical mediator for the production of type I interferons, eliciting strong immune responses. A new class of drugs that activate STING, generally named STING agonists, had already been used in vaccine adjuvants and cancer immunotherapy with enhanced immune responses, as a consequence of the boosted production of interferons that help regulate the immune system.

Recent studies have revealed that STING agonists induced the death of both normal and malignant B-cells. Although the apoptosis of normal B-cells hampered immune responses, these results revealed a new potential for STING agonists application in the treatment of certain types of lymphoma, leukemia, and multiple myeloma.

“In non-B-cells, STING agonists stimulate the production of interferons, but since they induce apoptosis in B-cells, these B-cells do not live long enough to help boost the immune response,” Chuh-Chi Andrew Hu, Ph.D., associate professor in the Translational Tumor Immunology program at The Wistar Institute and the study’s senior author, said in a press release. “We wanted to determine why STING agonists behave differently in normal and malignant B-cells and how to extend this cytotoxic activity in malignant B-cell leukemia, lymphoma, and multiple myeloma.”

Researchers found that the endoplasmic reticulum IRE-1/XBP-1 stress response pathway must be activated for normal STING function in non-B-cells. Cells lacking either IRE-1 or XBP-1 were not able to produce interferon in response to STING agonists. Additionally, IRE-1/XBP-1 pathway activation was required for the survival of B-cell leukemia, lymphoma, and myeloma cells, suggesting that lowering the activity of this signaling pathway may promote apoptosis of malignant B-cells.

Consistently, Hu and his colleagues demonstrated that the stimulation with STING agonists suppressed the IRE-1/XBP-1 pathway increasing the apoptosis of malignant B-cells. Such results were confirmed in mouse models of chronic lymphocytic leukemia and multiple myeloma, where mice treated with STING agonists showed regression of the B-cell malignancies.

Investigators raised an interesting question: How was STING able to promote type I interferon production in non-B-cells (mouse embryonic fibroblasts, melanoma, hepatoma, and Lewis lung carcinoma cells), but apoptosis in normal and malignant cells? The answer to this question was related to the inability of B-cells to efficiently degrade STING after stimulation with its antagonists.

“This specific cytotoxicity toward B-cells strongly supports the use of STING agonists in the treatment of B-cell hematologic malignancies,” said Chih-Hang Anthony Tang, M.D., Ph.D., the first author of the study. “We also believe that cytotoxicity in normal B-cells can be managed with the administration of intravenous immunoglobulin that can help maintain normal levels of antibodies while treatment is being administered. This is something we plan on studying further.”