Some with Smoldering Multiple Myeloma May Benefit from Immediate Treatment, Study Suggests

Written by |

Smoldering multiple myeloma (SMM) — an early, asymptomatic precursor of multiple myeloma — often exhibits similar genetic alterations as the full-blown disease, suggesting that patients could benefit from prompt treatment instead of waiting for symptoms to develop, research shows.

The findings are paving the way for tests designed to identify patients with SMM who already have the genetic mutations characteristic of multiple myeloma and are at high risk of disease progression.

The study, “Genomic patterns of progression in smoldering multiple myeloma,” was published in Nature Communications.

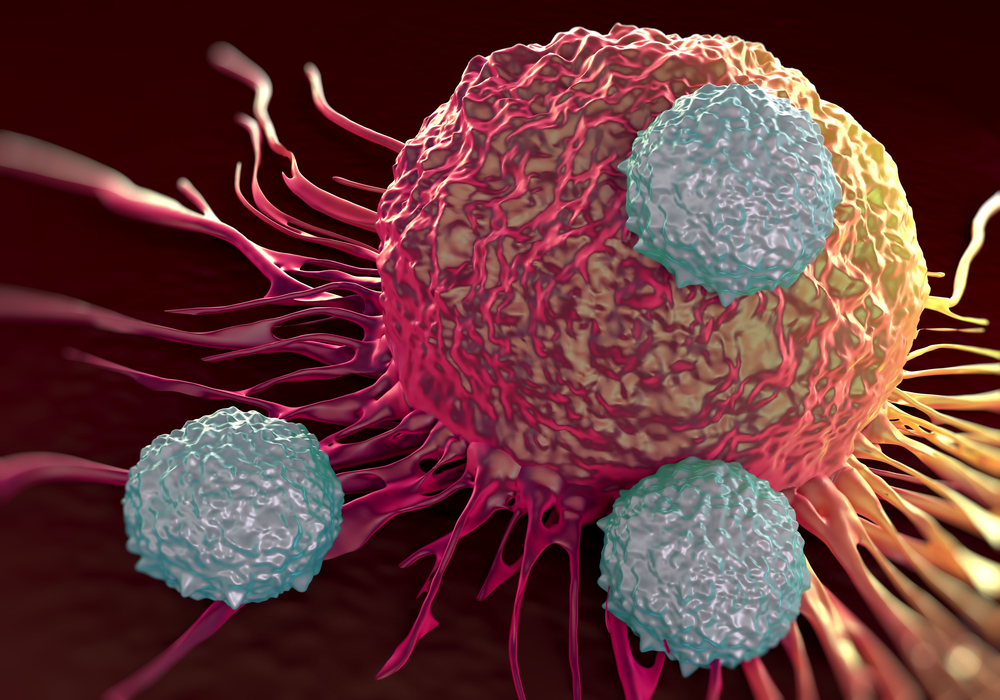

Smoldering multiple myeloma, a condition that usually precedes myeloma, is characterized by the rapid growth of plasma cells — the same type of blood cells that cause myeloma — that are still in a “premalignant state” and lack some features of “true” cancer cells.

SMM is puzzling to scientists because of its high degree of heterogeneity: while a percentage of patients diagnosed with SMM progress to symptomatic myeloma in a short period of time, there are others who experience practically no symptoms and whose disease comes to a halt or advances very slowly.

Now investigators, led by Nikhil Munshi, MD, PhD at the Jerome Lipper Multiple Myeloma Center at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, may have found the reason behind SMM variability and set the path for the development of tests to predict disease progression for individual patients.

The study enrolled 11 patients with SMM who developed myeloma within three years of diagnosis.

To analyze genetic alterations in plasma cells throughout disease progression, researchers collected different sets of samples: one when patients had been diagnosed with SMM and another after their myeloma diagnosis. Scientists then sequenced the genome of plasma cells to look for differences between the two stages of disease.

With this approach, researchers first found that the genetic composition of premalignant plasma cells in SMM is almost identical to that of myeloma cells.

They also described how SMM can progress in two ways: one in which the genetic composition of plasma cells practically does not change from SMM to myeloma and disease progression is rather fast (static progression model); and another in which the evolution of SMM to myeloma is accompanied by the appearance of new types of genetically different plasma cells and disease progression is usually slower.

“Our study shows, however, when the disease follows the static progression model, SMM is, from a genomic standpoint, myeloma. The advance of the disease is solely a matter of an accumulation of diseased tissue. For such patients, it may make sense to begin treatment soon,” Munshi, the senior author of the study, said in a press release.

“In the spontaneous evolution model, by contrast, SMM is genomically distinct from myeloma,” Munshi added. “It advances toward myeloma only when genetic mutations create new subsets of SMM cells that develop into myeloma. Treatment for such patients might involve agents that prevent such subsets from arising.”

Although it is not yet possible to determine whether a particular patient diagnosed with SMM will follow the static progression or spontaneous evolution model, Munshi said his team and collaborators are focusing their efforts to drive research further.

“These results suggest that multiple myeloma needs to be redefined to include some patients with smoldering myeloma, and points the way to new treatment approaches geared to the course of disease development in each patient,” Munshi said.