Adaptimmune Immunotherapy Increases Time It Takes for Myeloma to Progress, Trial Shows

Written by |

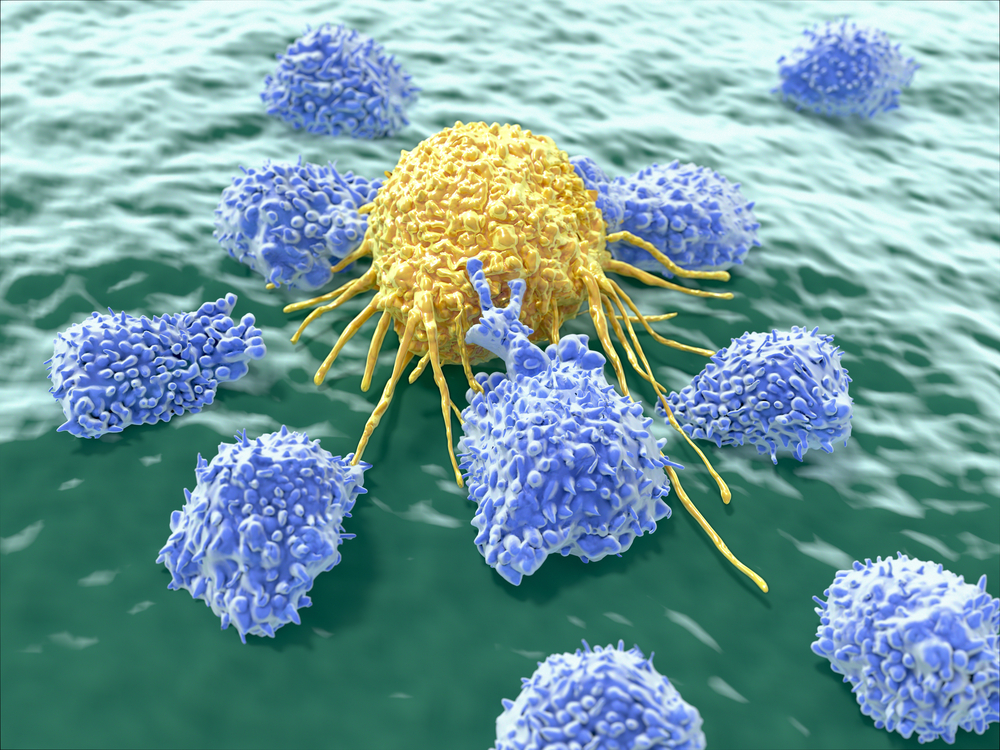

An Adaptimmune therapy that strengthens immune T-cells’ response to cancer has helped patients with advanced myeloma live as long as five years without their disease progressing, long-term results of a Phase 1/2a clinical trial show.

Another important finding was that the 25 patients, all of whom had received stem cell transplants, survived a median of three years after receiving Adaptimmune’s YY-ESO-1 SPEAR T-cell therapy. That’s several months longer than the 29 months the American Cancer society says is the average for the worst form of multiple myeloma, Stage 3.

The long-term results of the pilot study (NCT01352286) also showed that the immunotherapy has an acceptable safety profile.

Adaptimmune discussed the findings at the 59th American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting in San Diego, Dec. 7-12. The presentation was titled “Phase I/IIa Study of Genetically Engineered NY-ESO-1 SPEAR T-Cells Administered Following Autologous Stem Cell Transplant in HLA-a*02+ Patients with Advanced Multiple Myeloma: Long Term Follow-up  (NCT01352286).”

The patients’ high-risk or relapsed multiple myeloma had left them with few remaining treatment options and a low life expectancy.

All of the participants had tumors containing either the NY-ESO-1 or LAGE-1a proteins, or both. NY-ESO-1 and LAGE-1a are antigens — molecules that can trigger an immune response against the cancer cells that produce them. High levels of the molecules are associated with poor myeloma outcomes.

To increase the strength of T-cells’ bonds with cancer antigens, Adaptimune genetically modifies a patient’s T-cells to do a better job of recognizing an DNA sequence that both NY-ESO-1 and LAGE-1a have.

Patients received the modified T-cells two days after their stem cell transplants. Scientists have dubbed this type of therapy SPEAR, for specific peptide enhanced affinity receptor.

Seventy-six of the patients were continuing to respond to treatment at 100 days. The figure dropped to 44 percent by the end of a year, however.

The median time it took for patients’ myeloma to progress after treatment exceeded 12 months. Some patients’ cancer had not progressed after five years. At that point, 11 of the 25 patients were still alive.

Patients’ median overall survival was three years.

A measure of the immunotherapy’s safety was that there were no fatal adverse events from treatment. The most common adverse events included diarrhea and nausea, which all patients experienced; anemia, which occurred in 96 percent; loss of appetite, 92 percent; a blood clotting condition called thrombocytopenia, 92 percent; fatigue, 88 percent; fever, 84 percent; rash, 84 percent; low potassium levels, 76 percent; a type of fever known as febrile neutropenia, 72 percent; and vomiting, 72 percent. These adverse events were not unusual in this patient population.

Six patients developed a transplant complication called graft-versus-host disease, but treatments resolved it.

“Mature data from this study in multiple myeloma continues to show promising efficacy and acceptable safety,” Dr. Rafael Amado, Adaptimmune’s chief medical officer, said in a press release. “We have observed a high response rate, long response duration, and encouraging long‑term survival in this population of patients with poor prognosis, treatment refractory myeloma.

“In addition, NY-ESO SPEAR memory T-cells persist long term and respond to antigen after more than three years post-treatment,” he said.

Adaptimmune is also evaluating a combination of NY-ESO SPEAR T-cell therapy and Merck’s Keytruda (pembrolizumab) in a Phase 1 trial (NCT03168438) that involves multiple myeloma patients who have not received a stem cell transplant.